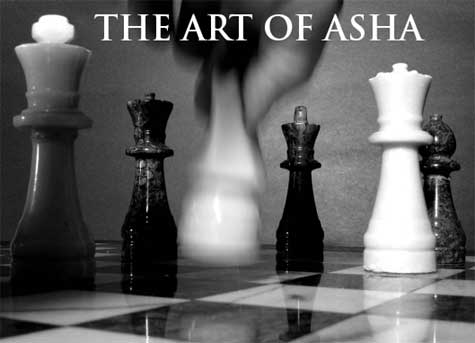

The Art of Asha

Lord Pentland had spoken about Legominisms being a way by which high initiates pass esoteric knowledge down through the centuries. I had asked, "Is chess a Legominism?" He nodded and several days later gave me a book about Asha, or chess, the royal game, the Game of Kings, thought to originate in India or Persia about 5,000 BCE. The book held that chess was a conscious construct that represented the laws and forces governing the world. The primary elements of chess are time, space, force and material. The white and black pieces symbolize the cosmic and natural forces which constantly struggle with one another for domination. The chessboard is composed of 64 black and white squares which theosophically add up to 10, or one and zero, all and everything and nothing. The board is composed of eight rows with eight squares each. Eight is the number of infinity and, when turned horizontally, the symbol of continual return. Each game is a microcosm of the archetypal struggle between Creation and Destruction, Good and Evil.

A LARGE BANNER, HIGH ATOP THE CHESS BOOTH, PROCLAIMED—

PLAY THE CHESS MASTERS

OF PERSIA

ONLY 50 CENTS!

The booth was one of many in a bustling bazaar of colorful booths and tents stretching the length of the entire block of 66th Street between Lexington and Park Avenues. Overnight, Lord Pentland's groups had transformed the street into a pungent and sumptuous Middle Eastern bazaar offering perfumes and pottery and carpets and candies and clothes and jewelry and belly dancing and fortune-telling and storytelling.

With the two "Persian chess masters" exhausted from a day of playing three boards at a time, and mostly getting beaten, Lord Pentland stepped into the booth to relieve them. Almost immediately a challenger came forward. He was a well-built man in his midforties. He had a hard, unforgiving warrior's face, broad forehead, square jaw, glasses and sharp direct eyes. I had the impression that this man had "crystallized" wrongly. He was dressed casually in a beige sweater, dark brown slacks and loafers, but there was nothing casual about him. His manner was aggressive, cocksure, even defiant.

"Game?" the man challenged.

Lord Pentland nodded, somewhat resignedly I thought. It was as if he knew this man, or this type of man, and had played him many times before. Lord Pentland silently set up the pieces, placing the white pieces on his side of the board. They stood facing one another.

"You always take white?" snapped the man.

Lord Pentland smiled benignly, but made no reply. He moved his king's pawn two squares to the center of the board as he had before.

The man's eyes glinted. Instead of countering on the wing with a pawn move, he immediately blocked white's advance by advancing the black king's pawn two squares. He pushed up the sleeves of his sweater, snatched a pack of cigarettes from a pocket, took out a cigarette, and crushed the empty pack, tossing it on the ground. He flicked a light from an expensive gold lighter, inhaled and awaited Lord Pentland's reply. The man gave off a strong animal energy. His movements were confident, powerful. There was a "knowing" about him. He was, to use Gurdjieff's phrase, a "power possessing being." The game evolved into the Four Knights game, symmetrical, a solid and conservative game. The man was no newcomer to the game of chess. He commanded his pieces with authority.

Some seven or eight moves into the game Lord Pentland blundered away a bishop. The man captured instantly with his knight, smacking it down on the board like a rifle shot. The sound hit me right in the stomach.

Lord Pentland, at least outwardly, remained impassive. But I felt inside he was working with his and the man's energy. A bishop down now, white had to go on the defensive. The tempo now was black's. The man quickly built up and consolidated his position, then mounted an attack into the heart of white's pieces. Fortunately, Lord Pentland had castled his king, but such was the force of the black attack that its forward momentum could only be stalled by the sacrifice of several pawns.

Given black's position and material advantage—white was a bishop and two pawns down—even a draw seemed unlikely. I thought it would be best to concede quickly rather than go through the ordeal of playing out a game that was clearly lost, and particularly so with this man. But Lord Pentland played on. I supposed it was in keeping with the Work. Those students who remained at the bazaar and were free of tasks gathered around the chess table. A student found a comfortable chair and set it down next to the board for Lord Pentland.

"Would you like a chair as well?" inquired Lord Pentland of the man politely.

The man ignored the question. He was bent over the board, bracing his body with one hand, the other on his hip. He had his win, and he wanted it. He was not going to be distracted.

A few moves later, Lord Pentland attempted to engage the man in a little conversation. Instead, the man held up his forearm, checking the time on his watch. His manner signaled impatience. In a clipped, implacable tone he stated:

"Have to be going soon. Let's get on with it."

—Excerpt from William Patrick Patterson's Eating The "I"