Fourth Way Perspectives

In Search of the Soul, Part X

Buddhism, Part II

Tibetan Buddhism

Tibetan Buddhism, with its tantric teachings and practices, remained shrouded in mystery and unavailable to the West for most of modern history. Yet it flourished for 14 centuries as the state religion of Tibet and was practiced in neighboring Bhutan, Sikkim and parts of Nepal as well. Surrounded on three sides by mountain ranges, Tibet remained remote and isolated from foreign influence until the mid-20th century, when Communist China invaded, repressing the Tibetan culture and religion, and forcing thousands of Tibetans, including the present Dalai Lama, to flee into exile.

Buddhism entered Tibet from India in the 7th century with the arrival of many Buddhist masters from renowned Indian schools. Over the centuries, four main schools of Tibetan Buddhism developed. The Geluk, or Yellow Hat School, the Dalai Lama's school, is the youngest of the four branches, dating back to the 14th century. The earliest school was the Nyingma, the Old Translation School or Ancient School, founded in the 8th century, followed by the Sakya School and the Kagyu or Red Hat School, with its deeply tantric roots. A council held from 817-836 ce resulted in the scrupulous translation of the Sanskrit Buddhist texts, as well as a wide range of other Buddhist literature, into Tibetan, which were then carefully preserved for centuries. From the 17th century until the invasion by China in 1949, the Dalai Lama of the Geluk school led the central government of Tibet from the city of Lhasa.

Like Zen, Tibetan Buddhism, known as Tantrayana or Vajrayana, is considered a specialized branch of Mahayana Buddhism, although it departs dramatically from many Mahayana traditions. The basis of Vajrayana Buddhism, the tantras, are revelations of the Buddha separate from the tradition of the sutras. The primary text, the Uttaratanta, is attributed to Maitreya, the future Buddha, with a commentary by Asanga, the 4th century founder of the Yogacara school in India. Asanga is said to have visited Maitreya in the Tusita heaven (the realm in which Maitreya resides as a bodhisattva awaiting his descent to earth 4,000 years after the Buddha's death), where Asanga was initiated into the mysteries of the tantra. Tibetan tradition is based on a full translation of the five treatises of Asanga's ancient Sanskrit text. According to Tibetan tradition, the conventional path described by

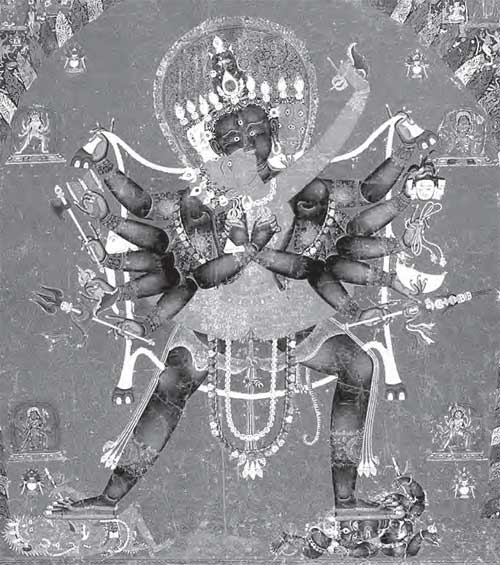

Chakrasamvara and Vajravarahi, Tibet, ca. 15th c., embody the enlightened Buddhas of the Highest Yoga Tantras, intended to lead the Tantric practitioner directly to enlightenment within this lifetime. Chakrasamvara practice places special emphasis on the attainment of the radiant light of bliss generated through the union of Chakrasamvara and Vajravarahi.

the Hinayana and Mahayana is a journey that is a long one, extended over innumerable lifetimes. Therefore, the Buddha taught the unconventional instructions of Vajrayana, known as the anutarra-yoga tantra (unsurpassable tantra) to provide a more direct route to enlightenment. In the Tibetan perspective, one follows the path to enlightenment by first practicing

Hinayana (the early teachings of the Four Noble Truths and Eightfold Path), then Mahayana (the bodhisattva vow), and finally Vajrayana (intensive meditation practice based on the tantras). Through practice of the "Highest Tantra Yoga Mantra," a highly developed practitioner can attain Buddhahood in one lifetime.

Tantric Roots

The roots of Tibetan Buddhism were in the tantric traditions of India, where Tantrayana or Vajrayana branches arose separately from the monastic practices of Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism. Vajrayana began with a small group of isolated meditators in the jungles of India who became siddhas (perfected ones) and were practitioners of the unconventional traditions of the highest or innermost tantras. The tantras were kept in deep secrecy and passed from master to disciple who learned to develop the miraculous powers of the siddha. These included levitation, the ability to be present at different places at once, distance vision, and the ability to travel through the air. Siddhas endured years of harsh deprivation and often practiced meditation and taught in cremation grounds. In both India and Tibet, tantrism developed two main branches, referred to as the Right-hand Path, characterized by philosophical treatises and strict discipline, and the Left-hand Path, whose followers emphasized ceremonies, direct experience (often of conflict) and sometimes ritual sexual practices.

Doctrinally, Vajrayana Buddhism differs from other branches of Mahayana in that it teaches that "everything is Nirvana." That is, the world of samsara is not something left behind to enter into Nirvana upon enlightenment; instead, the two realms are essentially one. Key to this is the teaching that everything is interconnected and there is no essence to anything.

Phenomena have no discoverable essence or real nature, but appear without any objectifiable reality, like reflections in a mirror, due to causes and conditions. Phenomena, having no objectifiable real nature, are not eternal, but neither are they merely nothing. They do not come from anywhere, nor do they go anywhere. There is not real arising of them, nor is there any actual passing away of them. They do not exist independently, but occur interrelatedly due to the presence of sources and appropriate conditions. Thus all phenomenal occurrences are beyond any possible conception.

The "science of death" and the impact of one's death on the next rebirth are of extreme importance in Tibetan Buddhism. Accounts of experiences natural to the pre-death and postdeath states have been kept for centuries as part of Tibetan Buddhism's esoteric teachings, The Tibetan Book of the Dead, or the Bardo Thodol, being the most well known of these. In these works, Tibetan Buddhists have mapped the physical and psychological stages of death in exhaustive detail. As part of their training, Tibetan monks studying the science of death at the highest levels train to help the spirit of a dying man leave its body through the top of the skull by learning to create an opening at the top of their own skull.

The doctrine of reincarnation, like the science of death, is highly developed in Tibetan Buddhism. As one Buddhist scholar describes it:

In the Tibetan view, our human state is only one among many possible modes of being. The Tibetans teach that our current human existence is one brief moment in a long spiritual journey comprised of millions of lives. We may be human beings at the moment, but since begininingless time, we have been trapped within the prison of samsara and have been cycling through its various types of existence. Within Tibetan tradition, samsara is seen as being composed of six realms, the three lower realms including hell-beings, the hungry ghosts and the animals, and the three higher realms, those of human beings, demi-gods and gods. Among all the possible samsaric states we could be born into, the human one is among the most rare. It is said that hell-beings are as numerous as dust particles in the entire universe, and hungry ghosts as plentiful as grains of sand in the river Ganges, and animal life teems in every drop of water or particle of earth. Even the gods may be compared to the number of snowflakes in a blizzard. In contrast, those endowed with blessed human life are as rare as stars in the noonday sky. Human birth is the most fortunate because, of all the six realms of being, it is the only one in which spiritual practice may be undertaken.