Fourth Way Perspectives

Film Review

Knowledge, Not Faith

Faithless

Directed by Liv Ullmann

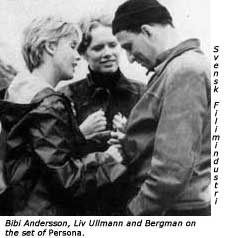

The greatest questions a human being can ask, if sincere, are is there a God? and Who am I? Few filmmakers, if any, have more relentlessly and intuitively struggled with these questions than the eighty-three-year-old Swede Ingmar Bergman, who after his masterful Fanny and Alexander some eighteen years ago, gave up filmmaking to retreat to Fårö (Sheep's Island), a rocky, windswept Baltic island. Beginning as a screenwriter with Svensk Filmindustri, Bergman's first filmed script in 1944 was Torment. Within a year he directed and wrote the screenplay for Crisis. In the next ten years he would write and direct eighteen more films before his Smiles of a Summer Night in 1955 brought the name Ingmar Bergman to international attention.

He might have made a career of writing and directing such light, pleasing fare, but instead, only a year later, came his hauntingly archetypal The Seventh Seal in which a medieval knight, Antonius Bloch, returns home from the Crusades to find a plague ravaging the land. Disillusioned, his once great faith wavering in the face of the pervasive human suffering and evil, the knight expresses timeless questions:

Why can't I kill God within me? Why does He live on in this painful way even though I curse him and want to tear him from my heart? Why, in spite of everything, is He a baffling reality that I can't shake off? I want knowledge, not faith.

The Virgin Spring followed just two years later—a medieval folk tale of a vain young girl who is raped and murdered on her way to Mass by two brutish shepherds. In a chilling display of concentrated savagery, the avenging father butchers her killers, only afterward to fall on his knees, his hands raised heavenwards in his anguish, beseeching God:

You saw it, God. The death of an innocent child, and my vengeance. You permitted it, and I don't understand you. Yet I now ask you for forgiveness—I do not know of any other way to reconcile myself with my own hands. I don't know of any other way to live.

The Question of God

This amazing ascent to the innermost regions of the essence continued with three films, usually taken as a trilogy, in which Bergman explored the question of God: Through a Glass Darkly (1961), Winter Light (1963) and The Silence (1964). In The Magic Lantern: An Autobiography he wrote:

I have struggled all my life with a tormented and joyless relationship with God. Faith and lack of faith, punishment, grace and rejection, all were real to me, all were imperative. My prayers stank of anguish, entreaty, trust, loathing and despair. God spoke, God said nothing. Do not turn from me Thy face.

I underwent an operation, a minor one, but I had to be anesthetized and, due to an error, was given too much anesthetic. Six hours of my life vanished. I don't remember any dreams; time ceased to exist, six hours, six micro-seconds—or eternity. The lost hours of that operation provided me with a calming message. You were born without purpose, you live without meaning, living is its own meaning. When you die, you are extinguished. From being you will be transformed to non-being. A god does not necessarily dwell among our increasingly capricious atoms. This insight has brought with it a certain security that has resolutely eliminated anguish and tumult, though on the other hand I have never denied my second (or first) life, that of the spirit.

Having conceived of God in the image of a spider in Through a Glass Darkly, in Winter Light he resolved his God question—"The film is the tombstone over a traumatic conflict which ran like an inflamed nerve throughout my conscious life. The images of God are shattered without my perception of Man as the bearer of a holy purpose being obliterated. The surgery has finally been completed." His notion of God now is reconciled in nothingness. In The Silence he depicts what remains. Two sisters, Anna and Ester (originally, Bergman conceived Ester as a man) and Anna's young son are forced by Ester's grave illness to stop in a foreign country preparing for war. The one sister is promiscuous, the other a lesbian, the boy entranced by the mother; it is a disturbing vision of people locked in their own worlds. Said Bergman: "This is hell—perversion of sex. When sex is completely totally isolated from other parts of life and all the emotions, it produces an enormous loneliness. That is what The Silence is about: the degradation of sex."

Having answered his God question for himself in the negative—though the aforementioned resolution is unconvincing—Bergman's second question, Who am I? can only be answered in terms of Man himself. And what he has found is a human spirit living in a meaningless world in which sex rules all and everything. Though interested in the occult through his study of the playwright August Strindberg—whose A Dream Play was Bergman's "great literary experience"—there is no indication that Bergman ever encountered the teaching of Mr. Gurdjieff. If he had, he would have seen that so much of what he worked his way to through his own suffered and contemplated experience is an integral part of The Fourth Way. Man is asleep, as Gurdjieff said. There is no one there, no real self-awareness, and so his dreams live out his life. A dream life, then, which has no meaning. And, yes, Gurdjieff would agree, "Sex plays a tremendous role in maintaining the mechanicalness of life. Everything people do is connected with 'sex': politics, religion, art, theater, music, is all 'sex'.... [It] is the center of gravity of all gatherings.... Sex: it is the principal motive force of all mechanicalness. All sleep, all hypnosis, depends on it."

Bergman obviously now saw sex as the mainspring and dilemma of human life, for after The Silence, in film after film, his questioning and exploration no longer centers on the metaphysical dimension but on human life itself— relationship, betrayal, loneliness, meaninglessness, the web of societal and personal lies which cauterize and buffer the conflicting conditions and roles humans must play.

Retreat to Fårö Island

Having stopped filmmaking in 1983, Bergman has spent the intervening years living alone on Fårö (his last wife the actress Ingrid Thulin died of cancer). Contemplating his life, at one point he decided to relive the story of his life through watching his films from first to last.

[When] I decided to 'hang up' the camera, I was able to view my work as a whole and began to realize that I did not mind talking about my past.... What I had not been able to anticipate was that this act of looking back would, at times, turn into a murderous and painful business. Murderous and painful give a rather violent impression, but those are the best words I can find for it....

Watching forty years of my work over the span of one year turned out to be unexpectedly upsetting, at times unbearable. I suddenly realized that my movies had mostly been conceived in the depths of my soul, in my heart, my brain, my nerves, my sex, and not the least, in my guts. A nameless desire gave them birth. Another desire, which can perhaps be called 'the joy of the craftsman,' brought them that further step where they were displayed to the world....

The truth is that I am forever living in my childhood, wandering through darkening apartments, strolling through quiet Uppsala streets, standing in front of the summer cottage and listening to the enormous double-trunk birch tree. I move with dizzying speed. Actually I am living permanently in my dream, from which I make brief forays into reality.

He took a great number of chances with his film career. The fear of failure, though always a concern, never stopped him. "Failure can have a fresh and astringent taste, adversity stirs up aggression and shakes life into creativity which might otherwise remain dormant. It's fun to cling to the northwest wall of Mount Everest. Before I am silenced for biological reasons, I very much want to be contradicted and questioned. Not just by myself. That happens every day. I want to be a pest, a troublemaker, and hard to pigeon-hole."

During this time he occasionally returned to the mainland to direct plays and TV dramas; he also wrote two film scripts, both of which he asked others to direct. The first, The Best Intentions (1992), was directed by Billie August. It explored the conflicts of class and psychology that divided Bergman's parents—his father was a strict and severe evangelical Lutheran clergyman from a poor background; his beautiful and adored mother was distant, closed and aristocratic. The unresolved tensions between the parents led, Bergman believed, to his being born into "a cold womb."

Notes

1. Intuitively struggled. Stig Bjorkman, Torsten Manns & Jonas Sima. Bergman on Bergman (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1970), p. 104. "One of my strongest cards," says Bergman, "—perhaps my strongest card of all—is that I never argue with my own intuition. I let it make all the decisions.... Over the years I've learned that so long as I'm not emotionally involved—which always clouds one's ability to decide matters intuitively—I can follow it with a fair degree of confidence."

2. Faith. "If you have faith, if you've some deep conviction, whether you're a Nazi or a Communist or what the hell else you are—then you can sacrifice both yourself and others to your faith. But from the moment you've no faith—from that moment you live in a deep inner confusion—from then on you're exposed to what Strindberg calls 'the powers.'" Ibid., p. 236.

3. The Seventh Seal. Made in 35 days, Bergman says it is "one of the few [of my] films really close to my heart. Actually, I don't know why. It's certainly far from perfect. But I find it even, strong, and vital. Furthermore, in this film I passionately cultivated my theme to the fullest.... I believe a human being carries his or her own holiness, which lies within the realm of the earth; there are no other worldly explanations. So in the film lives a remnant of my honest, childish piety lying peacefully alongside a harsh and rational perception of reality." Ingmar Bergman, Images: My Life in Film (New York: Arcade Publishing, 1990), pp. 235 & 238.

4. The Virgin Spring. Bergman doesn't think much of the film, not even including it in his 1990 book Images: My Life in Film. As early as 1968 he was saying, "Now I want to make it quite plain that The Virgin Spring must be regarded as an aberration. It's touristic, a lousy imitation of Kurosawa.... At the time I'd thought it a good film, one hell of a fine film! I considered it one of my best films. I thought it was magnificent. Only much later did I discover it was all exterior scenery and no inner content. It was a washout." Bergman on Bergman, pp. 120, 150.

5. Gave up filmmaking. Bergman's After the Rehearsal, originally made for television as was his Scenes from a Marriage (1973), was released as a film in 1984, but his final cinematic effort is Fanny and Alexander. Foreshadowing Faithless, the cheating husband asks near the end of Scenes from a Marriage, "Must it always be that two people who live together for a long time begin to tire of each other?"

6. I have struggled all my life. Ingmar Bergman, The Magic Lantern: An Autobiography (New York: Viking, 1988), p. 204.

7. Failure. Ingmar Bergman, The Magic Lantern, p. 255.

8. This is hell. Stuart M. Kaminsky, editor, Ingmar Bergman: Essays in Criticism (London: Oxford University Press, 1975).

9. A Dream Play. Bergman considers himself "a specialist" in Strindberg. As he says, "Strindberg has followed me all my life [he saw his first production of A Dream Play when he was twelve]. Sometimes I've felt deeply attracted to him, sometimes repelled." Bergman on Bergman, p. 23.

10. Sex plays a tremendous role. P. D. Ouspensky, In Search of the Miraculous, p. 254.

11. I decided in 1983. Ingmar Bergman, Images: My Life in Film, pp. 13, 14 and 17.

12. Strict and severe evangelical clergyman. Bergman was regularly beaten by his father for his misdeeds. He writes: "The immediate consequence of confessing was that you were frozen out. No one spoke or replied to you. As far as I can make out, the idea was to make the criminal long for punishment and forgiveness. After dinner and coffee, the parties were summoned to Father's room, where interrogation and confessions were renewed. After that, the carpet beater was brought in, and you yourself had to declare how many blows you felt you deserved. When the punishment quota had been established, a hard, green cushion was fetched, trousers and underpants pulled down, you prostrated yourself over the cushion, someone held firmly onto your neck, and the blows were administered. "I can't claim that it hurt all that much. The ritual and the humiliation were most painful.... After the blows had been administered, you had to kiss Father's hand, at which point forgiveness was declared and your burden of sin fell away, being replaced by deliverance and grace. Though of course you had to go to bed without supper and evening reading, the relief was nevertheless considerable." Ibid., p. 38.

13. Relives an early, haunting infidelity. The affair was with Gunilla Holger, the editor of a film magazine. Both were married at the time and as he says, "Our love tore our hearts apart and from the very beginning carried its own seeds of destruction." See The Magic Lantern, pp. 160–68.

14. Persona. "This film saved my life—that is no exaggeration. If I had not found the strength to make that film, I would probably have been all washed up. One significant point: for the first time I did not care in the least whether the result would be a commercial success. The gospel according to which one must be comprehensible at all costs, one that had been dinned into me ever since I worked as the lowliest manuscript slave could finally go to hell (which is where it belongs!). Today I feel that in Persona (1966)—and later in Cries and Whispers (1972)—I had gone as far as I could go. And that in these two instances, when working in total freedom, I touched wordless secrets that only the cinema can discover." Ibid., pp. 64–65.

15. One can change one's position. P. D. Ouspensky, In Search of the Miraculous, p. 255.