The Gurdjieff Legacy Foundation Archives

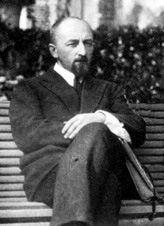

Thomas Alexandrovich de Hartmann (1885–1956)

Thomas de Hartmann was born on September 21, 1885, in Khoruzhivka, a small village east of Kiev in the Ukraine. He was born to an aristocratic Russian family. At the age of four he began piano lessons and in 1903, at the age of eighteen, he received his diploma from the St. Petersburg Conservatory. He was a graduate of the Imperial Conservatory of Music and studied composition with three of the greatest Russian composers of the 19th century—Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Anton Arensky and Sergei Teneyev.

In 1907, at the age of twenty-two, Thomas de Hartmann's ballet, The Pink Flower, was performed at the Imperial Opera House. Both Nijinsky and Karsavina were cast under Diaghilev's directorship. The Tsar was so impressed with de Hartmann's talent he personally granted the young composer a waver from military service to study composition in Munich under Felix von Mottl. In Munich, de Hartmann befriended poet Maria Rainer Rilke, painter Wassily Kandinsky, and artist and former Sufi Alexander de Salzmann, whom he later introduced to Gurdjieff. De Hartmann died in New York in 1956.

During a return visit to St. Petersburg, de Hartmann met and later married Olga Arkadaevna Schumacher, the daughter of a prominent government dignitary. The young couple returned to Munich, but World War I soon intervened and de Hartmann was ordered back to his regiment in St. Petersburg. As an officer of the Guards, he made several visits to the front. Despite being continually active in the war effort, he also managed to compose Forces de l'amour et de la sorcellerie, a marionette opera that was performed in St. Petersburg in 1915.1

In 1916, at the age of thirty-one, Thomas de Hartmann, already a recognized composer in Russia, met Gurdjieff through his acquaintance with Andrei Zakharov2, a mathematician by profession and student of Gurdjieff. Gurdjieff, aware of his background, had de Hartmann meet him in a café frequented by prostitutes3 and other low life on St. Petersburg's Nevsky Prospect. Gurdjieff asked him why he wished to join the Work. De Hartmann responded, "Although happily married with enough money to live on and a life of music, all this is not enough."4 He added, "without inner growth there is no life at all for me." In the memoir written with his wife, Our Life with Mr. Gurdjieff, de Hartmann described his life at this time as a search.5 Quoting a Russian fairy tale, "Go—not knowing where; bring—not knowing what; the path is long, the way unknown; the hero knows not how to arrive there by himself alone; he has to seek the guidance and help of Higher Forces." And so, following the abdication of the Tsar, Thomas and Olga de Hartmann followed Gurdjieff after he went to the Caucasus in 1917 and remained with him until 1929.

Thomas de Hartmann transcribed and co-wrote much of the music Gurdjieff collected and used for his movements exercises. This unique musical collaboration began in Essentuki in 1918 and continued until 1927, resulting in a remarkable oeuvre of over seven hundred compositions for piano. The music catalogue can be divided into two main parts: movements music and performance music. Gert-Jan Blom says of this music, "From an ethno-musicological perspective, the Gurdjieff /de Hartmann catalogue is a rich source of information about eastern ritual, folk and sacred music from a period of time before recorded music."6 The de Hartmanns remained with Gurdjieff at the Prieuré after the Institute was formally closed. Then, beginning in 1929 on a trip to New York, Gurdjieff began to speak to the de Hartmanns about arranging their lives separately from the Prieuré. Upon return, Gurdjieff made things very difficult for them, and they left. Mme de Hartmann wrote of her husband, "He could not even think of going back to the Prieuré once we had left, but his attitude toward the Teaching and Mr. Gurdjieff never changed."7 She stayed for a while longer, finally seeing the last of Gurdjieff as he left again for New York in 1930. In late October 1949, they received a call from Mme de Salzmann saying Gurdjieff was very ill and in the hospital. Though unwell, de Hartmann jumped out of bed, and they rushed to Paris. They were unable to see him, however, and he died the next morning. Thomas de Hartmann wrote the eulogy delivered at the funeral by the Russian priest.8

In 1950, de Hartmann compiled a collection of the compositions he had made together with Gurdjieff. During a visit to London, he said about his musical collaboration with Gurdjieff, "It is not my music; it is his. I have only picked up the master's handkerchief."9 In 1951, the de Hartmanns moved to New York to support groups there and in Canada, and to work with Mme Ouspensky.

Thomas de Hartmann wrote the draft of Our Life with Mr. Gurdjieff in Russian; he died unexpectedly in March 1956 before the book was completed. Olga de Hartmann finished the book and it was published in 1964 in English. In 1992 the Definitive Edition was published; it included unpublished material from the Russian manuscripts and material from Olga de Hartmann's memoirs. It is considered one of the most valuable documents on the teachings of Gurdjieff.

De Hartmann wrote of his experience in composing the music with Gurdjieff. After 1924, Gurdjieff turned away from writing music for the Movements, instead he would "create another kind of music."10

Once Mr. Gurdjieff said to me very sharply, "It must be done so that every idiot could play it." But God saved me from taking these words literally and from harmonizing the music as pieces are done for everybody's use. Here at last is one of the examples of his ability to 'entangle' people and to make them find the right way themselves by simultaneous work—in my case, notation of music and at the same time an exercise for catching and collecting everything that would be very easy to lose.11

Speaking to a group in Toronto, de Hartmann said,

How do we perceive an object? Why that one object, out of so many? Something connects us with that one object, and not with others. It attracts our attention. We pay attention to it. It attracts our attention through one of our senses: our eye, ear, nose, and so on. Our eye, ear or nose pays out attention to the object.

Our wishes, our desires, are connected with it in some way. We want to have it; or we want to avoid it; or we want to look at it more than we want to look at any other object.

This morning I saw a dog with two small boys. Its whole attention was glued to its two masters, watching to see what they would do, which way they would go, so he could quickly follow and be with them. He had attention for nothing else. And his attention continued to be concentrated on the two boys as long as I watched. This is already a high degree of attention, even if it is only animal attention—much stronger than many humans have.12

Notes

1. John Mangan, "Thomas de Hartmann: A Composer's Life," Gurdjieff International Review, Fall 2004, http://www.gurdjieff.org/mangan1.htm

2. Thomas and Olga de Hartmann, Our Life with Mr. Gurdjieff , ed. T.C. Daly and T.A.G. Daly (London: Arkana/Penguin Books, 1983), 1.

3. Mangan.

4. De Hartmann, 7.

5. Ibid., 5.

6. Gert-Jan Blom, Oriental Suite, The Complete Orchestral Music 1923–1924 (Netherlands: Basta AudioVisuals, 2006), 41.

7. De Hartmann, 254.

8. Ibid., 259.

9. Music for the Movements, Channel Crossings CCS15298, Wim van Dullemen , Quoted in the Historical Notes by James Moore and Jeffrey Somers for a Piano Recital, London 1988.

10. Ibid., 245.

11. Ibid., 246.

12. Thomas C. Daly and Thomas A.G. Daly, "On Thomas de Hartmann," Gurdjieff International Review, Summer 1999, http://www.gurdjieff.org/ourlife1.htm