Fourth Way Perspectives

Lord John Pentland: In Tribute

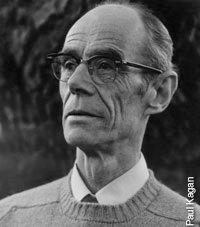

This year marks the 20th anniversary of the passing of Lord John Pentland, the remarkable man Mr. Gurdjieff chose to lead the work in America. Under his indefatigable leadership as president of the Gurdjieff Foundation of New York, from its inception in 1953 to his death 31 years later, the ancient teaching of The Fourth Way, rediscovered, reassembled and reformulated for modern times by George Ivanovitch Gurdjieff, grew significantly both in numbers of students and the establishment of foundations in many of the major cities of America. Gurdjieff had told Lord Pentland in the waning months of his life: "You are like Paul; you must spread my ideas."

This year marks the 20th anniversary of the passing of Lord John Pentland, the remarkable man Mr. Gurdjieff chose to lead the work in America. Under his indefatigable leadership as president of the Gurdjieff Foundation of New York, from its inception in 1953 to his death 31 years later, the ancient teaching of The Fourth Way, rediscovered, reassembled and reformulated for modern times by George Ivanovitch Gurdjieff, grew significantly both in numbers of students and the establishment of foundations in many of the major cities of America. Gurdjieff had told Lord Pentland in the waning months of his life: "You are like Paul; you must spread my ideas."

Gurdjieff's directive became his life's mission and responsibility, one that he never shirked. He became an unwavering and instrumental force in establishing the teaching and in doing so had to bring together and reconcile many disparate elements. Always diffident and respectful of others, he was open to new ideas and approaches but his perspective was always clear: the need to preserve the teaching and protect it from the introduction of distortions. He had to employ all his considerable political skills and organizational ability to guide the teaching through the many societal and psychic innovations and disturbances of the 1960s and 70s. Not everyone shared the same level of understanding, of course, and so some viewed him as too doctrinaire and unbending.

In February 1976 he had a heart attack. It must have been severe as a pacemaker was installed and he did not return to leading groups until the fall. For months everyone had anticipated his return and so one Sunday morning at the Foundation's estate at Armonk when the tall, thin and erect figure occupied the speaker's seat to open the day a breathless quality entered the room. What would he say after so many months? He spoke in an even tone as always, never excessively underscoring a point, but the theme of his remarks—the questioning of whether or not the Work had any longer a purpose to serve—hit like a bombshell for those who took it as a statement of fact rather than a theme of inquiry. That the man who had been instrumental in creating the Foundation could be questioning it's purpose was a red hot pepper for those who misunderstood the point he was making—that, just as a person, any spiritual or secular organization can become too fixed if it does not continually strive to keep its highest aim in view. It was a master stroke. The work he presented thereafter, rather than energy work that can induce imagination if not properly discriminated, was a reemphasis of core teachings and a probing of self-limiting identifications and beliefs.

The Gift of a Sheik's Hat

In Lord Pentland's final years a student had traveled to Kars, the ancient and remote village where Gurdjieff had grown up, and on his return had stopped in the city of Konya, Turkey, a Naqshbandi and Mevlevi dervish center. Seemingly by chance, he had met an old man on the back street of a bazaar who handcrafted dervish hats. He was the only one authorized to do so and the hats could only be sold with the permission of a sheik. Permission was granted for the purchase of a white sheik's hat. Upon the student's return, he presented it to Lord Pentland. Lord Pentland, who always eschewed ostentation of any type, was surprised and pleased. "He looked wonderful in it. Perfect...," the student recounted.

Lord Pentland died in Houston from a heart attack on Valentine's Day. It seemed fitting that the end came while he was on the road visiting groups. The funeral was held at St. Vincent Ferrer Roman Catholic Church in Manhattan only a few blocks from the New York Foundation. Following the initial Catholic ceremony, Lord Pentland's daughter, Mary Sinclair Rothenberg, walked to the pulpit and read from the Bible and then from Sword of the North, a novel about Prince Henry Sinclair, a thirteenth century warrior-chieftain and ancestor. The passage she read was of Prince Henry's death. Her voice was strong and clear and carried throughout the cavernous neo-gothic church. When she delivered the last line, however, her voice escaped her and the word dead shot into the high vaulting of the church and echoed down on the mourners in the pews.

Following her, Frank Sinclair, a longtime pupil of Lord Pentland's and a group leader but no relation, read from verses in Corinthians speaking of the vanity of man, the two bodies of man, one natural, the other spiritual. At the end of the reading, he noted that "Lord Pentland believed in the mystery of Resurrection."

William Segal, a close friend of Lord Pentland's and a senior group leader, spoke next. "Lord Pentland was the leader of the Gurdjieff Work in America," he said, "and a man who never spared himself in his role as a guide, as a teacher and as an administrator." He drew an intimate and loving portrait of his friend, explaining that Lord Pentland was much more carefree than many realized. "Lord Pentland was not afraid to laugh at himself," he said. The Saturday before his death, he said, he and some others had been with Lord Pentland when "a wellknown philosopher was introduced to him and said, ‘So you are the famous Lord Pentland!' and everyone laughed, especially Lord Pentland." He ended with the observation that in directing the work of the Gurdjieff Foundation, he had taken on "impossible challenges." He then added with emphasis, "Lord Pentland was not afraid to be misunderstood."

With the Ouspenskys

He was born Henry John Sinclair on June 6th in London and lived from the ages of 5 to 12 in India where his father served as governor general of the Indian state of Madras. On the death of his father in 1924, at age 18, he inherited the title of Lord Pentland. His family is from Edinburgh, Scotland, and the land known as the Pentland Hills. Not far away lies Rosslyn Chapel, dating from 1446 and built by his ancestor William St. Clair (more commonly, Sinclair), the Prince of Orkney.

Lord Pentland studied engineering at Trinity College, Cambridge, and graduated in 1929. He traveled widely and entered the worlds of business and politics. At 30 years of age in 1937 he attended a lecture by P. D. Ouspensky. Joining the Work, he regularly attended meetings and weekend work at Lyne Place outside of London. Of the thousand or so students Mr. Ouspensky had at the time, Lord Pentland became one of two deputized by Ouspensky to answer preliminary questions and do readings; the other was J. G. Bennett. With the war mounting, the Ouspenskys left for America in 1941.

Lord Pentland came to America to serve on the Combined Production and Resources Board, a cooperative effort of the U.S., England and France, and so was able to resume his work with the Ouspenskys. Besides meetings in New York City, a large farm/estate had been purchased at Mendham, New Jersey, for weekend work. As Mme Ouspensky's work was more practical than her husband's and stemmed directly from Gurdjieff, Lord Pentland came to feel much closer to her. She had become ill with Parkinson's disease and was largely confined to her bed. Nevertheless, she directed the household and the daily work. Of this time Lord Pentland wrote:

Madame, she was always called simply Madame, was constantly arranging conditions, whether through physical labor on the farm, through carefully formulated questions and messages to us, or through talks as we sat on the floor in her bedroom, which had the effect of miraculously renewing our energies and zest for living at the expense of the ugly and sleepy associations inside us. When we felt that renewal, she did not merely tell us to observe and record how it appeared, but confronted us with the questions: "What do you want?"... The meaning of Madame's question had to be felt inside. I heard it outside. So the question did not penetrate. It bounced.... I needed to free myself from a lot of unnecessary tensions and emotions even to have glimpses of the truth of Gurdjieff's ideas. I was facing my life as if it were a surface, oblivious of all the underside.

In late 1947 the shock of Ouspensky's death brought him to the realization that despite all the work he had done on himself, "I hadn't arrived at anything; I came to nothing." That is, like many others at the time, he had come to the place in which he felt his nothingness. Through Mme Ouspensky's introduction he went to Paris and met Mr. Gurdjieff. He found, as he said, that "Gurdjieff had an extraordinary quality of providing encouragement. People, he often used to say, were like motorists who were stalled on a highway for lack of gas and he would come and give them a fill-up." Eight years before, in 1941, Lord Pentland had married Lucy Babington Smith, another student, and a year later a daughter, Mary, was born.

In late 1947 the shock of Ouspensky's death brought him to the realization that despite all the work he had done on himself, "I hadn't arrived at anything; I came to nothing." That is, like many others at the time, he had come to the place in which he felt his nothingness. Through Mme Ouspensky's introduction he went to Paris and met Mr. Gurdjieff. He found, as he said, that "Gurdjieff had an extraordinary quality of providing encouragement. People, he often used to say, were like motorists who were stalled on a highway for lack of gas and he would come and give them a fill-up." Eight years before, in 1941, Lord Pentland had married Lucy Babington Smith, another student, and a year later a daughter, Mary, was born.

The couple took seven-year-old Mary to meet Gurdjieff at his apartment. Wrote Rina Hands of this time:

People are beginning to bring their children. They sit at the table with us and participate like everyone else, often being able to choose their idiots. There is a little English girl here at the moment, Lord Pentland's daughter, Mary Sinclair. Today she sat at lunch beside her mother and just in front of Mr. Gurdjieff. The meal was a long one and she was bored. She had been eating an orange and began to tear up the peel and scatter it on the table. Suddenly Mr. Gurdjieff spoke to her. "You know something," he said, "in life it is never possible to do everything." The child looked puzzled, as well she might. We all wondered what was coming. "You see," he went on, "on my table you cannot make this mess. Perhaps at home Mother permits. Then if you want to do this thing, you must stay at home. But if you stay at home, you will not be able to come here and see me. So you see, you can never do everything. Now put all orange back on plate and remember what I tell—never can we do everything in life." She did as she was told with a very good grace.... At the end of dinner, Mr. Gurdjieff asked her, "Who do you respect the most?" She did not understand and her mother said, "Who do you think is the most important person here?" Without a moment's hesitation, she replied, "My Daddy." I thought I detected a faint look of consternation on her mother's face, but she need not have had any qualms. Mr. Gurdjieff beamed at the child and said, "I am not offended. God is not offended either." He went on to explain that who loves his parents, loves God. If people love their parents all the time that their parents are alive, then, when their parents die, there is a space left in them for him to fill.

Lord Pentland was with Gurdjieff for about nine months before he died on October 29, 1949. He returned to New York and became a permanent resident. The Work being a work in life and not a withdrawal, in 1954 Lord Pentland founded the American British Electric Corporation which specialized in marketing British engineering services to American clients. He brought together a very loose arrangement of Gurdjieff people and groups formerly aligned with Orage, Ouspensky and others, a considerable task at the time, and oversaw the purchase of a large carriage house on the Upper East Side as the home of the Gurdjieff Foundation of New York. He understood the personal cost of taking on such enormous responsibilities for himself and others, for years later, looking back, he wrote: "...we are educated and tempted to seize the outer forms of responsibility too soon, before we have understood what is meant by them, to behave well, to keep one's chin up, to make up for one's faults by trying harder rather than accepting and seeing them, all the mannerisms that responsibility can take as a result of a formal education. The lopsidedness of these deeply embedded habits has to be seen again and again.... Otherwise, the assumption of outer responsibility may hide from them the subtle movement of wishing to work and not wishing."

As a teacher the qualities he emanated of integrity, resolution and restraint, together with his penetrating psychological insight into the origin of a student's foibles and pretences, made for a formidable presence. He had a gift for speaking in a way that eluded the jamming system of the formatory mind and went straight to essence. In his lectures what differentiated him was his ability to ground a subject and then probe it along its full scale before again returning to earth, the everyday. He was ever mindful in all he said and did to preserve intact those two separate lives in each person which Gurdjieff symbolized in Meetings with Remarkable Men as the sheep and the wolf. This is seen by all those who visit Lord Pentland's gravesite at the riverside cemetery of Valhalla, Westchester County, not far from his home in Riverdale. His gravestone stands on a gently sloping hillside by a large tree, overlooking a pond. It is a rose-tinted granite with a carved design, medieval in style, enclosed by a Celtic border. Within the border are two entwined dragons, one with a lamb's head, the other a wolf's. Between the lamb's and the wolf's heads is a fish which looks as though it had just escaped from water. Below lies the inscription:

Lord John Pentland 1907–1984

And his final message to all that

would hear.

Commit thy work to God.

—William Patrick Patterson

Notes

1.

You are like Paul. J.G. Bennett, Witness (Charles Town, W.Va.: Claymont Communications, 1983), p. 262.

2. A bombshell. William Patrick Patterson,

Eating The "I," p. 356.

3. White sheik's hat. Patterson, p. 348.

4. "I hadn't arrived at anything." Lord John Pentland, Interview, Telos [since renamed The Gurdjieff Journal] Vol. II, No. 3, p. 1.

5. Madame, she was always called simply Madame. Lord Pentland, private paper.

6. People are beginning to bring their children. Rina Hands, Diary of Madame Egout Pour Sweet: With Mr. Gurdjieff in Paris 1948–49 (Aurora, Ore.: Two Rivers Press, 1991), pp. 53–54.